Text: Forever in Kente: Ghanian Barbie and the

Fashioning of Identity

Author: Carol Magee

Carol Magee is an

associate professor at the University of North Carolina, in the US. She

specialises in African contemporary Art, with a focuses on photography. Magee

received her PhD from the University of California and she is currently serving

on the editorial boards of Athem Studies in Popular Culture and African Arts.

The article analyses

issues of nolstagia, imperialism and indentity in the Ghanian Barbie, and in

other ‘Dolls of the World’ collection dolls.

In the article, Magee

narrates when she came across the Ghanian Barbie, five months after she had returned

from her trip to Ghana. In a moment when she felt nostalgic for her time in

there. She explains that after analysing the cultural information on the

Ghanian Barbie box and on her clothing, she became aware of a greater cultural nostalgia

that was taking place.

She observes that the,

“Barbie is after all a fashion doll.” (MAGEE, 2005), and, for this reason, her

clothes are an important part of any analyses of the doll. The author mentions

that the Ghanian Barbie clothes are inspired on the Asante textile kente. An element that, according to her,

“evokes a cultutal/national heritage that, I argue, promotes a reductive,

essentialist notion of identity” (MAGEE, 2005) In contrast, the article

mentions another doll, Asha, an African-American friend of Barbie, that also

has kente in her outfit. However,

Magee explains that in this second case this element is “not reductive or

restrictive” (2005), as these two dolls, the Ghanian Barbie and Asha, embody

two very different identities and illustrate very distinguish perspectives of

world. Still, the author clarifies; both dolls expose the US domination in the

world.

The “Dolls of the

World” collection begun in 1980 and started being named “Princess Collection”

in 2001. This Mattel collector’s Edition represents fifty countries from every

continent. The dolls targets adults audiences and are not meant for playing.

“Instead, they are to be placed on a shelf, where a relationship is imagined,

rather than acted out with them.³” (MAGEE, 2005). For this reason, they are a

great example of past memories nostalgia.

Barbir has colonized the world!

The concept of

imperialism used in this article is explained as the process for which a

country dominates other country resources. Magee points out that, historically,

imperialistic dominations were primarily economic or political. However, in

reality, one cannot be separated from the other. One example of this is the US

imperialism and its promotion of democracy and capitalism. Using this idea,

Magee describes the world of Barbie and economic empire of Mattel. “Barbie is

sold in over 150 countries around the world, at a rate of two dolls per

second.” (Varney, 1998, pp. 163-64 apud Magee, 2005.). This way the author

establishes a connection between Barbie dolls and the spread of US cultural

concepts around the world, and along with it a US domination, imperialism.

However, the concept

of imperialism has evolved into a “New Imperialism”, whose concept focus on power

is expressed through culture and civilization. Magee notes that “Culture”

covers all the material production of a country and the symbolic meanings of

those products. She emphasizes: “(…), products convey messages beyond their

immediate and intentional meanings. Such non-overt meanings are frequently

naturalized; their social and political implications for relations of power are

not immediately, or necessarily, evident for either the producers or consumers.”

(Magee, 2005)

Barbie dolls are a

good example of how material objects can influence in a nation’s culture. Carol

Ockman, cited in the article by Magee, highlights the connection between the

doll and the ideal body type around the world, which is evolving towards a

westernized body type. Other sources reinforce this idea, as they reveal that Barbies,

even the “Dolls of the world” edition ones – which present cultural information

borrowed from other countries -, help to promote US culture and values. In

fact, the article describes Barbie as a symbol that reassures American

middle-class values and promotes US nationalism and sense of superiority. This way, the author questions what is the significance

of the Ghanian Barbie in this setting, and how her clothing reassures it?

Kente

Going deeper into the

discussion around the Ghanian Barbie and her kente inspired garment, Magee notes that the kente is a textile originally made to be wore by the Asante royalty and still is an

extremely important source of national and cultural pride in Ghana.

Ghanian former leader,

Kwame Nkrumah, appropriated the kente

as a national dress, which leaded, due to his association with Pan-Africanism,

to the association of kente not only

with Ghanian pride but also with African pride. Now, kente has become a symbol used in various ways by African-Americans

to express their pride, being the clothing the most visible one. This way, according

to Magee (2005), “kente has shifted

from identifying a social class(royalty) of an ethinic group (the Asante), to

also identifying a modern nation-state (Ghana), a continent (Africa), and a

diasporic population (African-Americans).”.

Barbie

Psychologists

affirm that playing with dolls that have the same colour as you help kids to

develop their sense of self-esteem. This is a privilege that African-Americans

started having access to in 1968, when Christie – an African-American friend of

Barbie- was launched. Yet, it was only in the 1980’s that African-American,

Asian and Hispanic Barbies appeared more regularly. Nevertheless, while,

according to DuCille (1994), the same brown plastic is used for all

African-American manifestations of Barbie, it is through the clothing that

ethnic and cultural differences are marked. Thus, within this context, the kente is used to express the African

heritage, the African-ness.

Going

almost against one of the most attractive features of Barbies - being easy to

be manipulated by the owner -, the Ghanian Barbie was designed “in such a way

as to discourage and/or prevent her from being undressed and her outfit

changed.” This means that this Barbie will remain always in a kente, and, for this reason, unlike her

fellow Asha; she cannot have more than one identity. Instead, she will always

have only one –cultural pride- aspect. She will never have any other

subjectivities that could be add to her personality.

Asha on her Kente outfit

Other dolls.

Magee mentions that

Mattel conducts a careful research while designing its dolls. As it is

extremely important for them not to be offensive. In especial, for the culture

who is being represented. However, even though the company did a great job

designing the Ghanian Barbie clothing, on the back of the doll’s box – blended

with some information about Ghana – is printed a Yoruba mask, from Nigeria.

The souvenir

The

“Dolls of the World” Barbies can be considered a souvenir, that is; an object

that serves the purpose of reminding one of a travel experience, a

childhood memory or of a place one

desires to visit. The relationship between a souvenir and its owner is usually

distance. Magee (2005) explains that this is necessary for if the relationship

achieve closeness the desire for the objected would be fulfilled and the

necessity of the souvenir eliminated. In this context, the Ghanian Barbir kente outfit and detailed accessories,

and the fact that her clothing can never – or are not supposed to – be removed,

will preserve the doll as an distant, different, foreign object – a souvenir.

The Collection

In

order to understand the meaning of a collection it is necessary to know how

that collection is organized. (Stewart, 1993, p. 154 apud Magee, 2005). In the

case of the “Dolls of the World” Collection, while some dolls are based on the

nation – Ghana, Italy, others are based on more specific locations – Paris,

Hawaii. However, when all the dolls are displayed together, their differences

are minimized and they all become part of the Barbie community. (Magee, 2005)

They look differente, but they are all clearly Barbies.

What

is interesting about the “Dolls of the World” collection is that they usually

invoke romanticized cultural elements from the past of the culture being

represented. That means that their costumes are usually based on references

from the past of ones culture, bringing traditional elements from the past to

the present. This way, their clothing, and consequently their identities, are

understand as a “time-locked view of ethnicity”. This instance of nostalgia

allows one to imagine a romanticized past with the culture being represented.

Which means, that in a setting where most of the “Dolls of the World” are

consumed in the US, this allows Americans to idealise a relationship with the

other country with who they become connected through the doll.

However,

it is important to note that, because the Barbies of the “Dolls of the World”

series are stuck in a romanticised past and identity, they do not exist in the

same reality as the “regular” Barbie does. In this context, and while the

regular Barbie can be considered an icon of feminine success – for all her

clothes and accessories are read as a sign of economic and social position, the

dolls of the World series are perceived as inferiors to the regular Barbie.

Some Brazilian Manisfestations of Barbie:

(They all represent a very especific social group or tradition. Although I am Brazilian I would not purchase any of these dolls for I do not identify with any of them)

Another

significant fact that Magee (2005) points out is that, differently from other

Barbie’s friends and family members who are meant to have their own identities,

the “Dolls of the World” do not have their own names. So, instead of having

proper names – such as Barbie’s Ghanaian friend Ama, they are named; Ghanian

Barbie, German Barbie, Chinese Barbie, Brazilian Barbie, between others. This is

interesting because it exposes the dominance of the Barbie – a US figure, over “others”.

Magee notes that “Without clearly delineated identities, it is easier to forget

the individuality of the peoples of those countries represented.” (Magee, 2005)

In the end, Magee meditates around the fact that the Dolls of the World dolls can serve as a 'distraction', as they allow the owners to create an imagined reality with the culture that the doll is representation, which keeps the owners distant from the true realities of the people being portrayed. Rather than a dicussion about the desig of the Dolls - if Mattel did or not a good job representing the cultures they intended to - this text reveberates if it is 'ok' to 'sell' this unrealistic - yet detailed - cultures.

In the end, Magee meditates around the fact that the Dolls of the World dolls can serve as a 'distraction', as they allow the owners to create an imagined reality with the culture that the doll is representation, which keeps the owners distant from the true realities of the people being portrayed. Rather than a dicussion about the desig of the Dolls - if Mattel did or not a good job representing the cultures they intended to - this text reveberates if it is 'ok' to 'sell' this unrealistic - yet detailed - cultures.

Some more Dolls of the World Barbies:

China

Australia

UK

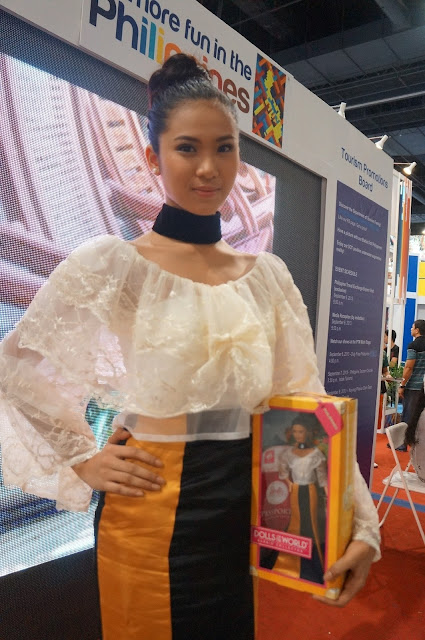

Philippines

Argentina

India

See more here: http://www.thebarbiecollection.com/gallery/dolls-of-the-world